BLF: How do you help your child understand that all feelings—even the big, hard ones—are welcome and valid?

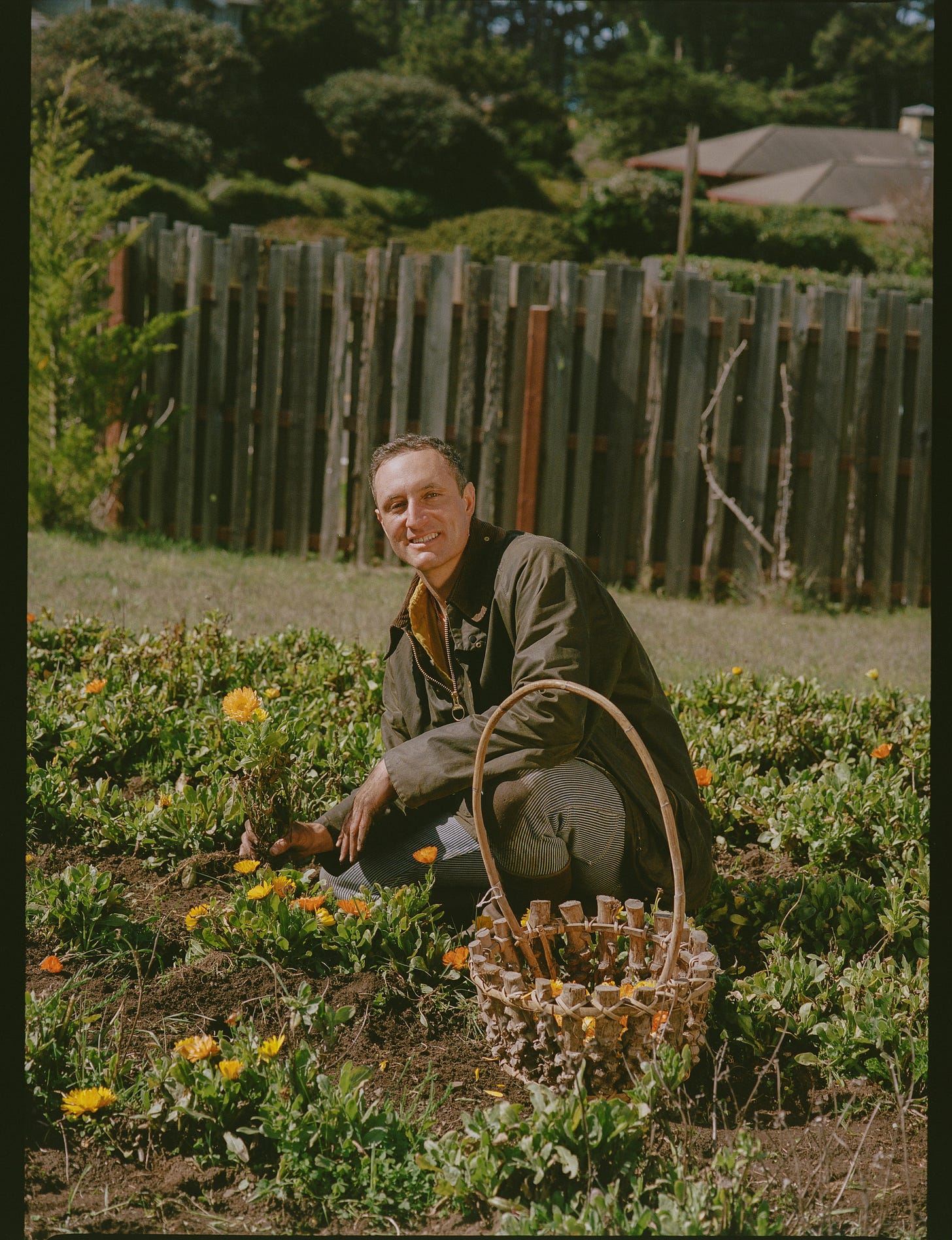

Dr. Max: I opened a medical practice out of my home so that children would feel safe and comfortable at the doctor’s office—it’s a space that feels more like a friend’s house than a clinic. If a child walks in and seems scared, we’ll often go outside first to meet the chickens or say hi to the cat. I’ve found that validating a child’s experience means completely reimagining what that experience looks like. I want the doctor’s office to feel like a place of curiosity, not fear—where their big feelings are not only expected, but embraced.

BLF: What are some tools or phrases you use to model emotional regulation at home?

Dr. Max: At home, we say a lot of: “It’s okay to feel that way.” And “I’m feeling ___ right now, and I’m going to take a moment before I decide what to do next.” It’s important to me that Esther grows up hearing adults narrate our own regulation—not just doing this behind closed doors, but outwardly showing them how we do it ourselves.

BLF: How do you talk to your kids about different kinds of families in a way that feels natural and affirming?

Dr. Max: Our child is still a baby, but we are already learning how to approach the question of how we built our family. I’ll be on a neighborhood walk with our child and have somebody affirm “You’re such a good dad- giving mom a rest and taking your baby out for a walk”. I’ve learned that if I shy away from this comment now, it will only make it harder and less natural to respond when my child is more alert. So I’ve really leaned into who I am as a gay father by affirming “We are a family of two dads, and my husband is making dinner so I decided to take our child out for a walk”. And at the same time, not feeling like my child is “missing a mom”. Because I’ve seen the faces of people who look disappointment and shocked by my response. If I can really own this now, and learn to interface with the outside world with affirmative and confident responses, then I believe my child will feel this, see this and hear this, and grow up understanding that each family composition is different, and it doesn’t mean one is better or worse than the other. And in this family, we have two dads.

BLF: Can you share a recent moment where you or your child felt proud, not just of who you are, but how you showed up emotionally?

Dr. Max: Esther is still a baby, but I already feel proud watching her make space for her feelings—especially the big, messy ones. The other day she was overtired and crying hard in my arms. Instead of rushing to “fix” it, I held her, told her, “You’re safe, I’ve got you,” and let her move through it. And by moving through it, she really just needed to move some poop through her descending colon. At that moment, I realized: my job isn’t to stop her from crying, but to let her move through the emotions so she can feel what is really going on- or that she was just constipated.

BLF: What do you wish more people understood about parenting as a queer or gender-diverse family?

Dr. Max: That it’s not about being different—it’s about being deeply intentional. Every part of queer parenting is chosen: how we build our families, how we show up in public spaces, how we teach our children to move through the world with pride and resilience. There’s so much joy and creativity in it—but also a constant awareness of how the world might perceive us. We don’t take any part of this journey for granted.

BLF: How are you creating space in your home for both joy and vulnerability?

Dr. Max: Our home is really an open door to our larger community of friends and family. It in fact feels like a hostel at times where we have all of the spare bedrooms taken up by friends from around the world. It brings a lot of joy to have this extended community contribute to our home through cooking, laughter, and sometimes cleaning up. But it also opens the door to real vulnerability- people see us at the end of the day, tired from work and just not feeling great. And it is in those moments that we really open up to our community and say “I’m tired, I’ve had a long day, I just need to lay down and rest. Can you just get dinner together and let me know when it’s ready”.

BLF: What role does community play in your parenting journey, especially during Pride Month?

Dr. Max: Community is everything. As queer parents, we don’t just parent within the walls of our home—we parent in relationship with the people who see us, celebrate us, and support us. Everybody can be part of our chosen family, and in fact, many people are. My husband runs an art non-profit out of our home and we constantly have friends from near and far who come to see us and stay with us. We’ve had artists paint newborn portraits of our child, and others who have knitted clothing, and others who just come by to bring food and conversation. And during Pride, we’re especially reminded of the generations who made this possible- for us to have a community and build a family that represents our truest selves.

BLF: What cycles are you actively working to break when it comes to emotional expression and gender norms?

Dr. Max: My own mother was an alcoholic and I spent a large portion of my childhood helping her through this disease. Yes, it was complicated, and I have a lot I could share about this. But her worst quality was that of a martyr. Her way of expressing love was by describing how much she had done for everybody but herself, and how beaten down she was by doing these things. It was rare to see her do anything with joy, and even though she always kept the house clean, homecooked meals on the table and laundry folded, it was always done with the weight of her neglecting her own self, her own health, and her own joy. And family traumas do live on through generations and I constantly have to check myself when I am picking up after my husband, or cooking a meal, that I am doing it with joy and not with a “woe is me” attitude. It’s small things, but it’s big energy, and I work on this every day.

BLF: How are you helping your kids build the language to name their feelings and identities confidently?

Dr. Max: We narrate everything. We don’t just say, “You’re upset”—we say, “It sounds like you’re frustrated because you wanted that toy back. That makes sense.” And as Esther gets older, we’ll continue naming feelings and identities as they arise.

BLF: Did you grow up in a home where dads didn’t cry? How are you rewriting that narrative?

Dr. Max: Absolutely. I rarely saw men cry growing up. And when they did, it was behind closed doors, quickly brushed off. In our home, I cry when I’m moved, or overwhelmed, or just need a release. Esther is going to see her dad—and her papa—feel all the things. That’s how we rewrite the narrative: by being living proof that masculinity and emotional depth aren’t opposites—they’re partners

I looooved this interview. Thank you so much for being so heartfelt and thoughtful.